Ray Stern | November 28, 2018 | 8:07am

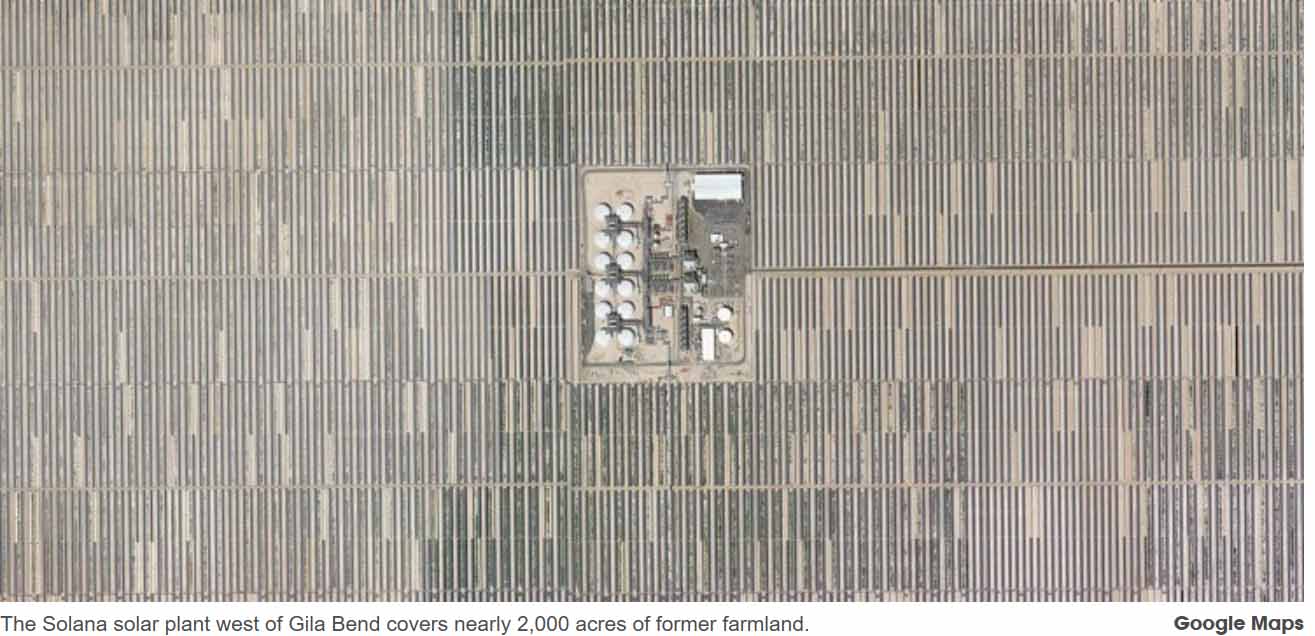

At about 9:40 a.m. on August 28, a toxic vapor cloud rose from the shiny rows of parabolic mirrors at the Solana concentrated solar plant just west of Gila Bend, Arizona.

Workers notified the control room, where managers immediately shut down the $2 billion plant, which was built by the Spanish firm Abengoa with help from U.S. taxpayers. The facility works by using its 900,000 mirrors to focus sunlight on pipes in front of the mirrors that contain "heat transfer fluid," (HTF), a toxic sludge that becomes super-heated by the sun's energy before being pumped to two 140-megawatt steam turbines.

That morning, according to county records, one of the larger, 2-inch feeder pipes developed a crack above a weld point and burst, spraying and spilling 1,000 gallons of molten HTF into the environment. Most went "into concrete containment and a fraction of this overtopped to soil," Carrolette Winstead of Abengoa told county officials in a September 7 email. Winstead estimated about 7 tons of material had been released.

Most of the release was in fluid form, but an estimated 2.6 tons evaporated into the air. About a quarter of the emissions were of biphenyl, a chemical sometimes used as a food preservative that's dangerous to breathe. No one was injured, but Maricopa County's air quality division issued the plant an initial notice of violation over the incident, which records show was self-reported by plant administrators.

The August incident was only the latest such problem to strike the plant, which had its first full year of operations in 2014. Its ongoing air-pollution incidents clearly complicate the idea of "clean energy." But the biggest challenge, stock filings reveal, is the weak performance that threatens Solana's financial viability.

As Phoenix New Times has reported since late 2014, the plant habitually generates less than 75 percent of the electricity that it's supposedly capable of cranking out.

The plant does have its benefits, even as an underachiever.

When most people think of solar power, they're thinking of photovoltaic solar panels. Solana's special skill is to keep making electricity for about six hours after solar panels quit for the day. The heat-transfer fluid running through the pipes at Solana stays hot in this overtime period, keeping those steam turbines turning. At its so-far theoretical max production level, Solana could pump out the same amount of electricity used each year by 71,000 households, according to Abengoa.

This photo from Solana plant operators submitted to the county shows a hairline crack above a weld in a pipe that burst, causing 1,000 gallons of heat transfer fluid to spill on August 28.

Maricopa County

Without additional battery storage, of course, Solana couldn't meet the actual electricity demand of even a single average Arizona household (about 14 megawatt hours), because it provides power for only part of a 24-hour day. But according to Arizona Public Service, it helps offset some of its power load in the evening.

Owned by a conglomerate of investors called Atlantica Yield, Solana agreed to sell its power to APS for 30 years. The utility estimated in 2013 that, on average, each customer pays about $1 extra per month because of Solana.

For that buck, APS customers can feel a warm fuzzy that a fraction of their kilowatt hours are generated with clean, Solana solar power. Except it's not always so clean. Solana has an unseemly air pollution problem.

In 2016, the county slapped the plant with a $1.5 million fine — the largest it's ever imposed. Leaking HTF was the culprit then, too.

A division manager for the county's air-quality department told New Times in 2016 that HTF released at the plant emitted twice as many volatile organic compounds than a natural-gas plant of the same size. (VOCs lead to ozone pollution).

Officials believe that nearby residents, had they been outside during Solana's emissions, could have smelled the chemical. The manager predicted that HTF pollution problems would continue.

In 2017, the plant self-reported three HTF leaks. Officials didn't fine Solana because plant operators were following the rules when equipment failed.

That was also the case with the August 28 spill, and the county didn't levy a fine. The plant was offline for two days until the weld on the pipe could be repaired.

Solana workers are accustomed to containing HTF spills, records show.

The 12-month "rolling total" for VOCs emitted by the plant — including the 2.6 tons released in August — was 17.2 tons as of September 11, plant officials reported to the county. The total amount of released "hazardous air pollutants," most of which is biphenyl, was 4.8 tons.

Emiliano Garcia, vice president of Atlantica Yield's North America operations, gave a brief response to questions about the plant's struggle with air pollution when contacted this week.

"As any industrial facility, we are exposed to equipment failures that could cause emissions," Garcia said. "Arizona Solar One is committed to minimize those failures and we are self-reporting, remediating any emissions, and working inside our permit parameters. The records are public and we follow strictly the legislation."

Garcia also addressed Solana's performance, which has not met expectations.

For 2016, the plant generated 643,443 megawatt hours. For 2017, it produced 724,505 — not much higher than the plant produced in 2015.

Garcia pointed out that 2016 and 2017 are not "representative" years for the plant. As New Times previously reported, a monsoon-driven microburst knocked out Solana for weeks in summer 2016. Two transformer fires in July 2017 cut the plant's production by more than half.

All these problems have been "completely solved," Garcia maintained.

They'd better be, public records show, if the plant is to remain viable. Atlantica Yield's March 2018 filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission acknowledges that "Solana has not yet achieved its technical capacity on a continuous basis," and that its financial health is on the line.

Because of the plant's under-production, Abengoa has been forced to make extra payments on Solana's considerable debt. In late 2017 and early 2018, the Spanish company paid an extra $120 million to compensate for the plant's lower-than-expected electricity output, records show. Starting in December, Abengoa must pay an additional $13 million per year for the next 10 years. But Atlantica Yield disclosed to investors that it can't guarantee Abengoa will fulfill that obligation.

If it doesn't, "Solana may have a negative financial impact or may not reach its target production, which could have a material adverse effect on our results of operations and cash flows."

Furthermore, the plant's "underperformance" could cause it to stumble on obligations to Liberty Interactive Corporation, which made a $300 million investment in the plant — a situation that would "adversely affect the cash flows expected from that project."

On the plus side for the plant: The filing shows that plant will pay no federal taxes for the next 10 years.

Garcia agreed that the SEC filing describes that Solana "performed below expectations" in 2016 and 2017. But he emphasized the 2018 numbers, which show that Solana may be on its way to a record production year. The plant has produced 655,344 megawatt hours so far this year, according to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's Electric Quarterly Report site. The output for July to September this year has already broken its record for the same time in previous years, Garcia noted.

Even if it sets a new record in 2018, Solana will fall well short of its 900,000-plus goal for generated megawatt hours.

And it will still have its troublesome, ironic, air-pollution problem.