More than 1 million US homes have solar systems installed on their rooftops. Batteries are set to join many of them, giving homeowners the ability to not only generate but also store their electricity on-site. And once that happens, customers can drastically reduce their reliance on the grid.

It's great news for those receiving utility bills. It's possible armageddon for utilities.

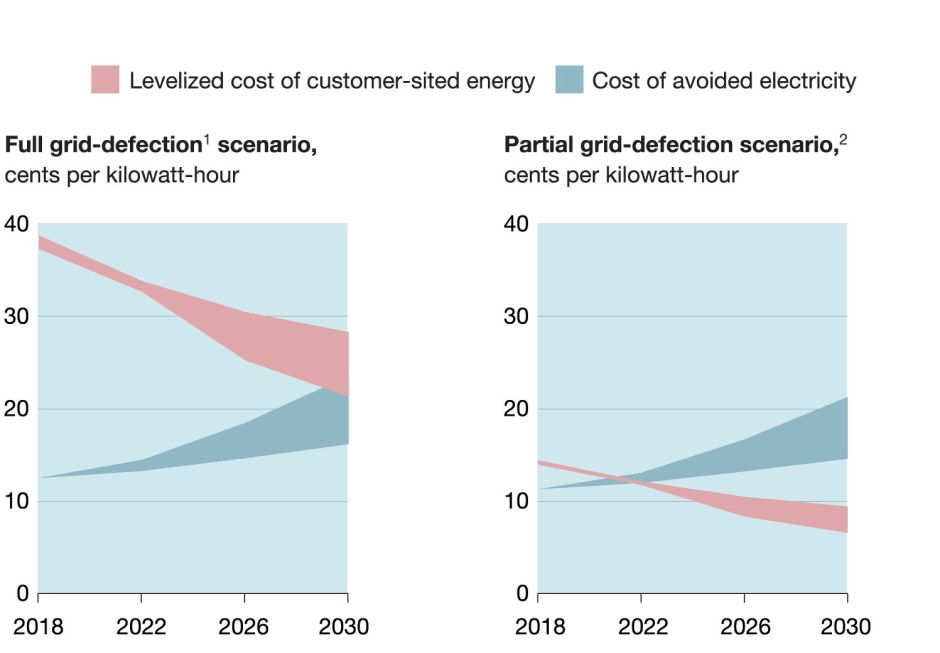

A new study by the consulting firm McKinsey modeled two scenarios: one in which homeowners leave the electrical grid entirely, and one in which they obtain most of their power through solar and battery storage but keep a backup connection to the grid.

Given the current costs of generating and storing power at home, even residents of sunny Arizona would not have much economic incentive to leave the electric-power system completely - full grid-defection, as McKinsey refers to it -until around 2028. But partial defection, where some homeowners generate and store 80% to 90% of their electricity on site and use the grid only as a backup, makes economic sense as early as 2020.

This scenario is already playing out in Australia and Hawaii, and has begun spreading to solar-friendly markets such as Arizona, California, Nevada, and New York. As batteries get cheaper and better, utilities are rattled at the prospect of losing a massive share of their revenue.

A self-reinforcing cycle is at work. As consumers make their own energy, rates must increase on those left to cover the system's fixed costs. This raises rates still further, making it even more advantageous for customers to leave the grid.

Instead of adapting to this dynamic, utilities have generally sought to stifle solar with time-of-use pricing, demand charges, or cutting compensation for electricity exported back to the grid.

But as daily needs for many are supplied instead by solar and batteries, McKinsey predicts the electrical grid will be repurposed as an enormous, sophisticated backup. Utilities would step up and supply power during the few days or weeks per year when distributed systems run out of juice. Our analysis helps show the grid is very valuable as a backup investment, says Amy Wagner, a co-author of the McKinsey report.

Only, the business models of utilities are not designed for this. Their revenue typically depends on selling kilowatt hours: more electricity equals more money for utilities. Power users don't respond quickly to daily price spikes in their power bill, so ratepayers absorb electricity costs. That goes away in a world where software managing a grid connection can automatically switch to batteries to avoid high charges. A new business model is needed.

The only way to pay for the grid is as a network, said McKinsey's David Frankel, a co-author of the report. "It's very counter to what the industry has seen." Instead of paying per kilowatt, he suggests, grid users could pay for access and reliability, with one fee covering the vast majority of usage. The model might resemble the fixed, monthly charges we're used to paying for cell phone data and calls.

At the moment, only a tiny fraction of utility customers have left the grid or installed batteries. But it's happening faster than was expected several years ago. Solar panels and battery prices are dropping fast - lithium-ion batteries have fallen from $1,000 to $230 per kilowatt-hour since 2010 - as massive new solar and battery factories come online in China and the US. By 2020, Greentech Media projects, homes and businesses will have more battery storage for energy (841 megawatts of capacity) than utilities themselves.

Utilities may find they need to retool their business models sooner than they think.

From