©2001 This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

©2001 This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Go to Sidebar 1, Maintain Temperature Stratification in Your Tank

Go to Sidebar 2, Rust Never Sleeps: Open Loop vs. Closed Loop

Hot water represents the second largest energy consumer in American households. A typical 80 gallon (300 l) electric hot water tank serving a family of four will consume approximately 150 million BTUs in its seven year lifetime. This will cost approximately US$3,600 (at US$0.08 per KWH), not accounting for fuel cost increases. Then it will be replaced by another one just like it. Hmm. Maybe we should rethink this...

An investment in a solar water heating system will beat the stock market any day, any decade, risk free. Initial return on investment is on the order of 15 percent, tax-free, and goes up as gas and electricity prices climb. Many states have tax credits and other incentives to sweeten those numbers even more. What are we waiting for? Forget the stock market. If you have invested in a house, your next investment should be in solar hot water.

In this article I'm going to cover the most common options for solar water heating, basic principles of operation, and some historical perspective on what has worked and what has not.

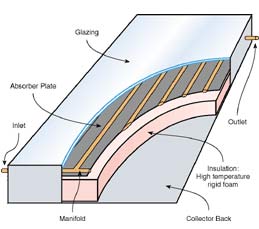

Below: A Typical Solar Flat Plate Water Heater.

A Checkered Past, A Bright Future

A Checkered Past, A Bright Future

Solar thermal's past is a good example of why everyone should be skeptical of government involvement in energy. Lucrative federal and state tax credits for solar energy were initiated under President Jimmy Carter in the '70s, and abruptly eliminated under President Ronald Reagan in 1985. This dealt the solar industry a devastating "one-two punch" from which it still has not recovered.

The intention was to stimulate sales for solar thermal systems. But the tax credits resulted in an aggressive promotion of tax credits rather than solar energy. The infant industry was overwhelmed to meet the demand. The demand vanished when tax credits were eliminated, and a majority of solar thermal companies went out of business. Thousands of orphaned solar thermal systems were left behind looking for a service technician.

The solar thermal industry has been purged of the tax credit telemarketers and overnight experts. Today's solar thermal industry includes reliable, efficient products and well-seasoned professionals who have seen it all. Solar hot water is one of the best investments you can make for your house and for the environment.

First Things First

First Things First

The best savings in hot water come from no cost or low cost options. Before you tackle solar hot water, take these steps:

- Turn the thermostat down. Many water heaters are set to between 140 and 180°F (60 and 82°C). See how low you can go. Try 125°F (52°C) for starters. A hot tub is 106°F (41°C). How much hotter do you need?

- Wrap the water heater with insulation. Insulated water heater "blankets" are usually available where water heaters are sold. (Be careful with natural gas or propane fired water tanks. They use an open flame to heat the water. You need to provide a space for air at the bottom of the tank, and at the top where the flue exits the tank. Safety comes before efficiency!)

- Fix those drips. They may not look like much, but they are a constant and persistent drain on your water heating load, and they waste water too.

- Use flow restrictors and faucet aerators to reduce your hot water consumption.

- Find other ways to use less hot water. Wash only full loads of clothes and dishes.

- Insulate your hot water pipes.

How Large a Solar Hot Water System Do You Need?

Hot water usage in the U.S. is typically 15 to 30 gallons (55-110 l) per person per day for home use. This includes primarily bathing, clothes washing, and dishwashing. But your commitment to efficiency has a lot to do with your actual usage.

Below: A 40 gallon batch heater.

The hot water tank is usually sized to handle one day's worth of consumption. So for a household of four, it would be reasonable to use an 80 gallon (300 l) tank based on daily hot water requirements of 20 gallons (75 l) per person per day.

The hot water tank is usually sized to handle one day's worth of consumption. So for a household of four, it would be reasonable to use an 80 gallon (300 l) tank based on daily hot water requirements of 20 gallons (75 l) per person per day.

Smitty and Chuck at AAA Solar in Albuquerque have put forth generally accepted rules of thumb for solar thermal collector sizing based on your climatic region:

- In the Sunbelt, use 1 square foot (0.09 m2) of collector per 2 gallons (7.6 l) of tank capacity (daily household usage).

- In the Southeast and mountain states, use 1 square foot of collector per 1.5 gallons (5.7 l) of tank capacity.

- In the Midwest and Atlantic states, use 1 square foot of collector per 1.0 gallon (3.8 l) of tank capacity.

- In New England and the Northwest, use 1 square foot of collector per 0.75 gallon (2.8 l) of tank capacity.

Based on these rules of thumb, a household of four with an 80 gallon (300 l) tank will need approximately 40 square feet (3.7 m2) of collector in Arizona, 55 square feet (5.1 m2) of collector in South Carolina, 80 square feet (7.4 m2) of collector in Iowa, and 106 square feet (9.8 m2) of collector in Vermont.

Of course, these are big ballpark calculations that will be affected by your incoming water temperature, hot water temperature setpoint, actual usage, and the intensity of the solar resource at your site. You should generally expect that this will give you 100 percent of your hot water in the summer and about 40 percent of your hot water year-round.

Your Choices–An Overview

Your Choices–An Overview

The type of system you choose will depend mostly on your climate. Freeze-free environments allow for simple, low cost designs. A batch heater uses a storage tank as a collector. A direct pump system circulates water from a collector to a storage tank. A thermosiphon system requires no pump for circulation, just the natural flow of gravity.

Most systems will require some measure of freeze protection. Drainback and closed loop systems with antifreeze and heat exchangers are the best choice for freezing locations. The extra parts increase cost and reduce efficiency, but since one frozen moment can turn into a disaster, it's worth the cost.

Direct pump recirculation systems, which circulate hot water through the collector, are often used where freezing is an infrequent occurrence. That's a risky strategy. Draindown systems, designed to drain water from the collectors to avoid freezing, were the most problematic of system designs. Many were removed or converted. Phase change systems, which in theory could collect heat at night using a refrigerant, never made it into the mainstream of commercial viability. Many of the lessons learned in solar hot water are presented in a publication Solar Hot Water Systems: Lessons Learned, by Tom Lane (see Access).

Solar Batch Heaters

The KISS (keep it simple, stupid) rule applies to solar heating. The batch water heater is the simplest of solar hot water systems. Once affectionately referred to as the breadbox water heater by the do-it-yourself (DIY) community, it has become known as the ICS (integrated collector and storage) water heater in the commercial industry. Its simple design consists of a tank of water within a glass-covered insulated enclosure carefully aimed at the sun.

Cold water, which normally goes to the bottom of your conventional water heater, is detoured to the batch heater first. There it bakes in the sun all day long, and is preheated to whatever temperature the sun is able to provide. Water only flows when used. House water pressure causes the supply of new cold water to flow to the inlet of the batch heater, the lower of the two ports.

Simultaneously, the hottest water exits from the higher port. It flows to the input of the existing water heater, which now serves as a backup to finish the heating job as required. Solar preheated water has become the cold water input to the existing water heater. You save whatever the sun is able to provide. And you still get all the hot water you ask for–it's that simple.

Below: Solar Bypass Valve Configurations.

Bypass Valves

Bypass Valves

A solar bypass is a series of three valves that allow you to bypass the existing water heater. You can shut it down when the solar collector will do the job alone, such as during summer months or utility blackouts. This is a manually operated configuration; just close off the inlet and outlet valve to the existing tank and open the center valve. This allows hot water to pass directly from the solar batch heater to the house.

Caution! These systems produce very hot water! A tempering valve is your protection from being scalded at the tap. You will regularly see temperatures in excess of 160°F (71°C) in summer months, which is much hotter than you are accustomed to getting from your conventional thermostatically controlled water heater. The tempering valve limits the temperature delivered to the tap by mixing in cold water as necessary.

A pressure temperature relief valve (PTRV) must be installed at the hot water outlet of the batch heater in case temperatures or pressures become excessive. You will find one of these valves installed on every conventional hot water tank too. It is a safety measure required by code. This valve only operates in an emergency, and is often replaced if it opens.

Who Can Use a Batch Heater?

Batch heaters are most appropriate for two to four person households (30 to 40 gallon (110-150 l) daily hot water requirement) in climates where freezing is infrequent. Their size is generally limited because the tank is built into the collector.

Multiple collectors can be installed in series for larger capacities. The outlet of the first collector becomes the inlet of the second in order to deliver higher temperatures. Before you put too many on your roof, consider that a 40 gallon (150 l) batch heater will weigh approximately 500 pounds (225 kg).

Some batch heaters have survived the coldest of winters with freeze-free performance because the large mass of the water tank is quite freeze tolerant. But plumbing lines to and from the tank are very vulnerable. You can make it work with a special selective surface on the tank, a well-insulated, double glazed collector, a whole lot of well-sealed pipe insulation (try R-30 or better), heat tape on the pipe, and good karma.

Are you arrogant enough to tempt Mother Nature to turn your water heater into a frozen fountain? Or are you prepared to drain the collector seasonally? If not, this system is not recommended for climates that freeze regularly.

Separate Collector & Storage

The simple design of a batch heater compromises the effectiveness of collector and storage functions. Heating the whole tank of water all at once will take all day to produce useful temperatures. Once hot, you had better use that hot water at the end of the day before the poorly insulated tank loses its precious heat to the cold night sky.

Most solar hot water system designs separate the collector from the storage tank. This can optimize both functions. Why not bring the tank in from the cold, insulate it well, and leave the collectors out in the sun where they belong?

What are the other advantages of separating the collector from the storage tank? Increase the surface area of a collector, compared to the amount of water being heated, and its temperature will rise more quickly. Configure the storage tank to keep the hottest water apart from the coldest water in the tank and you'll have hotter water available sooner. (See sidebar Maintain Temperature Stratification In Your Tank.)

There are also advantages in freezing climates. By separating the collector from the tank, you can put your tank and piping indoors out of a freezing environment, and insulate them better for greater efficiency.

Below: Two roof-mounted flat plate collectors.

Flat Plate Collectors

Flat Plate Collectors

Flat plate collectors are the most common solar thermal collectors. They are most appropriate for low temperature applications (under 140°F; 60°C), such as domestic hot water and space heating.

A flat plate solar thermal collector usually consists of copper tubes fitted to a flat absorber plate. The most common configuration is a series of parallel tubes connected at each end by two pipes, the inlet and outlet manifolds. The flat plate assembly is contained within an insulated box, and covered with low-iron, tempered glass. (See the diagram on page 45.)

The most efficient collector design maximizes solar heat gain, minimizes heat losses, and provides for the most efficient heat transfer from absorber plate to tube. Operating temperatures up to 250°F (121°C) are obtainable, although neither common nor desirable. Remember, you want hot water, not steam.

Selective Surface

A selective surface, often referred to as "black chrome" is far more efficient than a black painted absorber surface. Although a black surface is most efficient at absorbing solar radiation and converting it to heat, it is also highly efficient at re-radiating long wave infrared heat back out. These losses reduce collector efficiency.

A highly polished chrome surface would re-radiate the least infrared heat energy, but of course not being black, it would absorb very little. A selective surface combines the best of both worlds; high absorptance with low emittance. Sound high-tech? It's been around since the 1950s, and is used on most commercially available flat plate collectors. Its performance is worth the marginal additional cost, particularly in cold climates where radiant heat loss is greatest.

Below: A Thermomax evacuated tube collector.

Evacuated Tube Collectors

Evacuated Tube Collectors

If you want the highest efficiency solar thermal collector, you'll be interested in an evacuated tube collector, such as the one manufactured by Thermomax. Although evacuated tube collectors are more efficient than conventional flat plate collectors, they cost approximately twice as much per square foot.

Each tube and fin of the collector is contained within a glass tube from which all the air has been evacuated. Why? Air carries heat from the hot surface of the tube to the cooler surface of the glass to accelerate heat loss by convection. Eliminate the air and you have eliminated convective heat loss.

To minimize radiant heat loss, the tube is covered with a selective surface. Evacuated tube collectors are most appropriate for high temperature applications (over 140°F; 60°C). They are useful for more common low temperature applications too, such as domestic water and space heating.

Below: Direct Pump Recirculation System.

Collector to Tank Interface

Collector to Tank Interface

With the collector and the storage tank separated, the system design must provide a flow of water (or antifreeze) from tank to collector and return. Small circulating pumps provide the necessary flow with very modest energy requirements. Small hot water systems may use a direct current (DC) circulating pump powered by a single PV module (10 to 30 watts depending upon power requirements). You may be able to do without the pump altogether if you design for natural thermosiphon flow.

Thermosiphon System:

Natural Flow Powered by Gravity

Gravity powers convective flow in a thermosiphon system. Water in the collector becomes buoyant as it is heated, and it rises to an elevated tank. Cooler, heavier water falls from the tank to take its place. For best results, place the top of the collectors at least one foot (30 cm) below the bottom of the tank. Greater height differential will result in greater flow. Larger pipe, shorter runs, and gentle bends will make for an adequate flow rate.

If you require freeze protection, it's not hard to do. The collectors can be filled with an antifreeze solution (propylene glycol is the most common). The heat can be transferred to the domestic water via a heat exchanger.

Direct Pump Recirculation

The direct pump system uses an electric circulating pump to move heat from the collector to the storage tank. This means that you are free from the constraint of placing the collector below the tank, as required for thermosiphon flow. The pump can move heat from the collectors on the roof to a storage tank in the basement. Good sense still calls for minimal length of pipe run for efficiency.

A differential controller turns the circulating pump on or off as required. There are two sensors, one at the outlet of the collectors, and the other at the bottom of the tank. They signal the controller to turn the pump on when the collector outlet is 20°F (11°C) warmer than the bottom of the tank. It shuts off when the temperature differential is reduced to 5°F (2.8°C). Some systems let you adjust this hysteresis.

Below: Closed Loop Antifreeze Heat Exchanger System.

In climates where freezing occurs infrequently, a recirculation-type differential control will turn the circulating pump on when the collector inlet temperature falls to 40°F (4.4°C). The philosophy behind this design is that the cost of heating your collectors with hot water from your tank is low cost freeze protection if only required occasionally.

In climates where freezing occurs infrequently, a recirculation-type differential control will turn the circulating pump on when the collector inlet temperature falls to 40°F (4.4°C). The philosophy behind this design is that the cost of heating your collectors with hot water from your tank is low cost freeze protection if only required occasionally.

These systems were commonly used in the sunbelt, and only where freezing is a rare occasion. Recirculation systems are no longer very commonly used due to vulnerability to freezing as a result of power outages, malfunction of sensor or controller, or damaged sensor wires.

Draindown System (Not Recommended)

A draindown system is an open loop system in which the collectors are filled with domestic water under house pressure when there is no danger of freezing. Once the system is filled, a differential controller operates a pump to move water from the tank through the collectors.

A draindown valve, invented in the 1970s exclusively for these systems, provides the freeze protection function. When the collector inlet temperature falls to 40°F (4.4°C), the draindown valve, activated by the controller, isolates the collector inlet and outlet from the tank. It simultaneously opens a valve that allows water in the collector to drain away. A vacuum breaker is always installed at the top of the collectors to allow air to enter the collectors at the top so water can drain out the bottom. Right next to the vacuum breaker, you'll find an automatic air vent to allow air to escape when the system fills again.

Draindown systems have proven to be the most problematic of all freeze protection systems. They are vulnerable to frozen vacuum breakers and air vents, damaged sensors or wiring, lack of proper pipe drainage, and malfunctions with the draindown valve. This type of system is rarely installed new any more, and is not recommended. Many were converted to drainback or closed-loop antifreeze systems.

Closed Loop Antifreeze Heat Exchanger

Closed loop antifreeze systems provide the most reliable protection from freezing. These systems circulate an antifreeze solution through the collectors and a heat exchanger. Propylene glycol is the most common antifreeze solution. Unlike ethylene glycol (used in automobile radiators), propylene glycol is not toxic.

The closed loop antifreeze systems generally have the most parts. You'll find an expansion tank to allow the antifreeze to expand and contract with temperature change. You'll find a pressure relief valve to protect against excessive pressures in the closed loop; a spring-loaded check valve to prevent reverse flow of the closed loop at night so the collectors won't dissipate the heat from the water heater; an air vent and/or air eliminator to help get the air out of the closed loop (air is your enemy–it can block fluid flow through the system); and a pressure gauge so you can tell if your system is still charged. A couple of temperature gauges are a good idea in any system so you can tell how well your system is operating.

There's also one more assembly of fittings. Two boiler drains with a shutoff valve in between will allow you to charge the system with your charging pump. Once ready to charge the closed loop with your antifreeze solution, a charging pump is used to circulate the fluid throughout the loop, expelling all the air in the process.

Closed loop systems like this are quite common, whether they be for solar domestic hot water, radiant floor heating, or hydronic baseboard heating. Despite the many additional parts and fittings, they have a high degree of reliability, and are well understood by heating contractors.

Below: Closed Loop Drainback System

There is a downside to the closed loop antifreeze system design. Once a solar water heating system has satisfied its daily responsibilities, the system stops circulating. Without circulation to remove heat from the collectors, temperatures can climb to as high as 400°F (204°C).

There is a downside to the closed loop antifreeze system design. Once a solar water heating system has satisfied its daily responsibilities, the system stops circulating. Without circulation to remove heat from the collectors, temperatures can climb to as high as 400°F (204°C).

These high stagnation temperatures, as they are called, can cause problems with air pockets and breakdown of glycol antifreeze solutions. Air pockets form because high temperatures drive dissolved gases out of solution. Systems using propylene glycol as the antifreeze may use an inhibitor additive to prolong the life of the glycol. Otherwise, the glycol can break down, resulting in a sludgy deposit. Silicon and hydrocarbon oils have been used to avoid these problems, but they are expensive and are incompatible with seals and gaskets found in most off-the-shelf components.

Drainback: A Simpler Closed Loop

Although similar in name to the draindown type system, the drainback system is far different and much more reliable. It also provides some advantages over the closed loop antifreeze system. Drainback systems may use water as the heat transfer fluid, since the collectors drain when not in operation. Antifreeze provides an extra measure of freeze protection from poor drainage and controller or sensor malfunctions.

A circulating pump operated by a differential control is turned on when the collector outlet is at least 20°F (11°C) warmer than the tank outlet. Water or an antifreeze solution is lifted from a small reservoir tank and circulated through the collectors and back to the tank. Heat is transferred to the domestic water via a heat exchanger in the reservoir tank. The circulation loop through the collectors is a closed loop. The water or antifreeze solution is installed at the time of installation, and does not present a recurring supply of oxygen.

A drainback system requires a larger pump than any of the other systems described here. It must have sufficient capacity to lift the fluid to the highest point in the system. When there is no more heat to be collected, the controller turns the pump off, and all the fluid drains back to the reservoir tank. The collectors are empty. They can't freeze, and they can't overheat the antifreeze. As a DIY homeowner, you won't need a special charging pump either. When it comes time to change the antifreeze, you can just drain and refill the reservoir tank.

Solar Hot Water System Types: Advantages & Disadvantages

| System Type | Characteristic & Use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Solar Batch Water Heater | Open loop; Integrated collector & storage; Freeze protection generally limited to infrequent or light freeze climates | Simple; No moving parts | Freeze protection typically poor; Inefficient in cold climates; Small systems only |

| Thermosiphon | Typically open loop; May be closed loop with heat exchanger & antifreeze | Simple; Requires no electricity for operation | Collector must be located below tank; Inappropriate for use with hard water (open loop system) |

| Direct Pump System | Open loop; Freeze-free climates | Flexible placement of tank & collector; can be powered by PV | No freeze protection; Inappropriate for use with hard water |

| Direct Pump Recirculation System | Open loop; Climates where freezing is an unexpected occasion | Simple; can be powered by PV | Freeze protection is limited to infrequent & light freezes; Inappropriate for use with hard water |

| Draindown | Open loop; Designed to drain water when near freezing | Can be powered by PV | Freeze protection is vulnerable to numerous problems; Collectors & piping must have adequate slope to drain; Inappropriate for use with hard water |

| Closed Loop Heat Exchanger | Closed loop; Cold climates | Very good freeze protection; Basic principles well understood by conventional plumbing trades; No problems with hard water; can be powered by PV | Most complex of all systems, with many parts; Heat exchanger & antifreeze reduce efficiency; Fluid may break down at high stagnation temperatures |

| Drainback | Closed loop; Cold climates | Very good freeze protection if used with antifreeze; No problems with hard water; Simplest of reliable freeze protection systems; Fluid not subject to stagnation temperatures; Simple to homebrew; can be powered by PV | Heat exchanger & antifreeze reduce efficiency; Collectors & piping must have adequate slope to drain; Requires larger pump to lift |

The Choice is Yours

The system you choose will be determined first by whether you need freeze protection. If you live in a freeze-free climate, choose a batch heater or small thermosiphon unit for small systems serving one to three people. Larger needs can be met with an open loop direct pump system circulating water from storage tank to flat plat collector.

If you need freeze protection or have hard water, choose one of the closed loop systems with antifreeze and a heat exchanger. Either one will heat your water without fear of freezing.

Solar hot water is a good investment. Whether you are a do-it-yourselfer with plumbing skills or want hire a professional installer, I suggest you locate a dealer who serves your area. Ask their professional advice. Find out the products and services they have to offer, and which is the best fit for your needs and climate. Contact the American Solar Energy Society or the Solar Energy Industries Association for assistance in locating a contractor or supplier in your area.

Sidebar 1

Maintain Temperature Stratification in Your Tank

Hot water returning from the collector should enter the storage tank about a third of the way down from the top. This water may not be the hottest water you have collected all day, because solar insolation and outside ambient temperatures vary during the day. You don’t want this water to disturb the water at the very top of the storage tank. Draw water for use from the very top of the tank. That is where it’s the hottest.

When hot water is drawn from the tank, it is replaced by new cold water, which should enter at the very bottom. Water circulating to the solar collector should be drawn from the bottom of the tank. Why? Efficiency! Always supply your collector with the coolest water you have available. The cooler a solar collector runs, the less heat it loses to the surrounding environment.

Sidebar 2

Rust Never Sleeps: Open Loop vs. Closed Loop

A “hydronic” system is one that uses a liquid as its heat transfer medium. The most common alternatives to hydronic systems are air systems. Hydronic systems are nearly always categorized as “open loop” or “closed loop”—often referred to as “direct” or “indirect” respectively. If you are not aware of the difference between these, you run the risk of discovering one day that your system has been eaten alive by a slow yet persistent killer—oxygen.

Open Loop

Open loop systems are subject to a periodic fresh supply of oxygen, ready to trash every bit of cast iron, steel, or other corrodible part in your system. Whenever you draw water at the tap or bath, new water simultaneously moves in to replace it. Along with that new water comes a fresh supply of oxygen.

You have two lines of defense against damage by corrosive oxygen. You can prevent oxygen from entering the system, or you can use materials that are resistant to corrosion. Copper, bronze, brass, stainless steel, plastic, and the glass lining of a hot water tank have no problem with oxygen. Use these materials when dealing with fresh water supplies associated with “open” or “direct” systems.

Closed Loop

If your system is a “closed system,” you won’t have to worry about oxygen. You will be able to use cast iron components (pumps), which can save you money. Closed systems are charged with fluid at the time of installation. As a permanent part of the installed system, new oxygen is not introduced, and corrosion is not a problem. Read on and you will see several examples of open and closed systems.

Another important consideration with open or direct systems is whether or not you have hard water. Over time, calcium deposits from hard water will clog the collectors, ruining them. These deposits can be removed with periodic use of a descaling solution. But if you have hard water, you’ll be better off with a closed loop system.

Access

Ken Olson, SoL Energy, PO Box 217, Carbondale, CO 81623 · Fax: 559-751-2001 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.solenergy.org

AAA Solar Supply Inc., 2021 Zearing NW, Albuquerque, NM 87104 · 800-245-0311 or 505 243-4900 · Fax: 505-243-0885 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.aaasolar.com · For more design and schematic detail click on "Design Guide" then "Hot Water."

Thermo Technologies, 5560 Sterrett Pl., Suite 115, Columbia, MD 21044 · 800-7SOLAR7 or 410-997-0778 · Fax: 410-997-0779 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.thermotechs.com · Thermomax evacuated tube collector

American Solar Energy Society, 2400 Central Ave. G-1, Boulder, CO 80301· 303-443-3130 · Fax: 303-443-3212 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.ases.org

Solar Energy Industries Association, 1616 H St. NW, 8th Floor, Washington, DC 20006 · 202-628-7745 · Fax: 202-628-7779 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.seia.org

Tom Lane, Energy Conservation Services of North Florida Inc., 6120 SW 13th St., Gainesville, FL 32608 · 352-377-8866 · This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. · www.ecs-solar.com

©1995 - 2001 Home Power magazine. All rights reserved.

©1995 - 2001 Home Power magazine. All rights reserved.